T: 01822 851370 E: [email protected]

Visit RSN Survey about life in rural England to find out more.

Spotlight on RSN Member Insights - April 2020

RSN Member Insights is the place to discover the statistics that define communities within our membership. It is regularly updated with new analyses, and these will be highlighted in the 'What's New' section of the RSN's Weekly Rural Bulletin. The Rural Bulletin also provides the most relevant rural news to our member organisations, if your organisation is in membership with the RSN, subscribe and encourage your colleagues to read our invaluable rural weekly periodical.

In this edition of the 'Spotlight on RSN Member Insights', Dan Worth, our Research and Performance Analyst explores the statistics that point to the potential vulnerabilities that rural communities and residents might be facing in light of the coronavirus pandemic and resulting lockdown.

Background

The coronavirus pandemic is a challenge that everyone is having to tackle in the best way they can, no matter what their circumstance or location. Service providers are rising to the demands that defeating the progress of the virus present to their daily function, as well as being presented with new and varied challenges in the drive to support their communities and those most vulnerable within them at this unprecedented time.

Within this universally testing moment in history, our rural communities are having to react to challenges that are unique to their demographic and economic situations, as well as the variability in access to key services.

Demography

People of all ages can be infected by the new coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Older people, and people with pre-existing medical conditions (such as asthma, diabetes, heart disease) appear to be more vulnerable to becoming severely ill with the virus. In 2018, over 65s accounted for 23.7% of the predominantly rural population, compared with 15.9% for predominantly urban. 28.0% of England's over 65 population live in predominantly rural local authority areas, that is some 2.9 million people. Although social distancing may be more easily achieved in the rural context, it is clear from the higher proportion of the population being older, that rural areas need to work equally hard at controlling the spread of the virus to protect their health services.

The age of the population is only one side of the coin when considering the potential impact of coronavirus in rural areas. People with pre-existing medical conditions are more vulnerable to becoming severely ill. Life expectancies at birth for males and females stand at 80 and 84 years respectively, with healthy life expectancies at 64 and 65 years respectively in predominantly rural areas. Therefore the average number of years lived in poor health are 16 years for males and 19 years for females for those living in these rural local authority areas. Combining this with the propensity for a higher proportion of older people to live in rural locations demonstrates the importance of social distancing, but also highlights the potential additional burden and costs involved in 'shielding' the most vulnerable in rural communities.

Social distancing can be more difficult for older people where they share households with other people. Census 2011 data shows that those over the age of 65 are less likely in the predominantly rural context to live in a one person household.

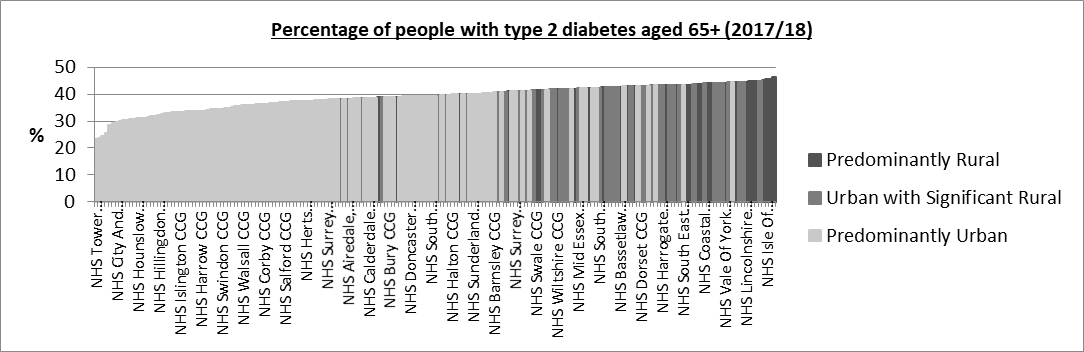

Public Health outcome indicators show that the percentage of population with a long-term health problem or disability is higher in predominantly rural areas than predominantly urban. By way of example, this is particularly evident in the percentage of people with type 2 diabetes aged 65+ (2017/18)

In addition to age and health being pre-determinates of serious illness from coronavirus, there is some evidence that men are more susceptible to becoming severely ill with the virus (although once again susceptibility increases with age). In 2018, 50.7% of the male population in predominantly rural areas were over the age of 45. This compares with 38.7% for the predominantly urban context.

Mental Health

With an ongoing lockdown and the persistent spectre of coronavirus hanging over every citizen, care for our mental health and wellbeing has never been more important. Mental health issues in rural areas are sometimes hidden or go unreported, but there are statistics available that provide clues to underlying issues that will need to be considered both during and after the pandemic.

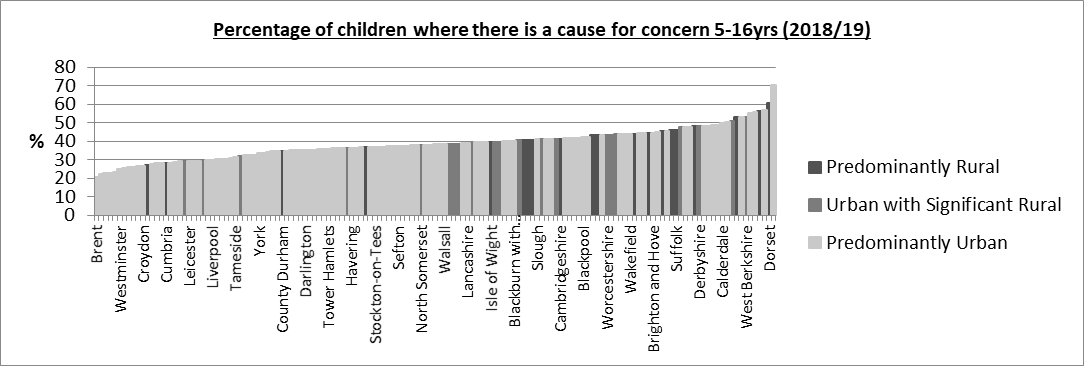

In 2018, the percentage of primary school pupils with social, emotional and mental health needs was greater for predominantly rural areas than predominantly urban. Likewise , the percentage of children where there was a cause for concern in the ages 5 - 16 years stood at an average of 42% in predominantly rural areas and 38% in predominantly urban (2018/19).

In 2017/18 hospital admissions for mental health conditions (under 18 yrs) per 100,000 stood at 95.9 in predominantly rural areas and 81.9 in predominantly urban areas, and hospital admissions as a result of self-harm (10-24 yrs) per 100,000 stood at 484.5 in predominantly rural areas and 415.2 in predominantly urban areas.

Recorded prevalence of depression in those aged 18+ (2017/18) was also greater in predominantly rural areas than predominantly urban.

Prevalence of loneliness data taken from the Census 2011 indicate that for those aged 65 and over, those people in rural locations are predicted by this measure to be less lonely. This may be explained by the higher proportions of similar age group living rurally, or the smaller communities engaging more actively over all age groups. Starting from this lower level of predicted loneliness however, could the effects of the social distancing and shielding that have become the new normal be having a disproportionate negative effect on the mental health of those aged 65 and over in rural communities where they had previously been socially active?

Action in tackling the mental health issues brought about or exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic will be putting strain on rural health providers both now and into the future. Of particular concern going forward will be the effects this pandemic will have had on the mental health of children who are now distanced from their peer groups, friends and teachers, and whose parents themselves may be going through very tough times.

Economy

Rural economies are distinct to one another depending on the situation locally, however they share some common differences with economies found in urban areas. It follows therefore that the effects on rural economies of the social distancing and business restrictions brought about by the pandemic will be variable across the rural piece, yet common in some shared differences to urban economies. Any remedial actions will hence require broad brush as well as targeted approaches to ensure most benefit to each individual community dependent on their economic situation.

To better understand the economic landscape in your area, do check the analyses in the Member Insights section at:

https://rsnonline.org.uk/category/economy-insights

Looking at some specific areas of interest regarding the rural economy in light of the restrictions in place, there are a number indicators that point to why and in what form current and future assistance to rural areas will be required.

The Annual Population Survey (Oct 2018 - Sep 2019) shows that the percentage in employment who are self employed (aged 16+) is greater in rural areas, with 18.3% being self employed in predominantly rural areas, and 14.6% being self employed in predominantly urban areas.

Workplace based median gross annual earnings continue to be lower for predominantly rural areas than predominantly urban. In 2019 such earnings stood at £24,300 for predominantly urban (excluding London) and £22,500 for predominantly rural.

Taking data from the 2018 Business Register and Employment Survey, rural areas have a smaller proportion of employees employed in the public sector, predominantly rural with a proportion of 15%, by comparison predominantly urban with a proportion of 17%. Civil service employment as a percentage of working age population (aged 16 - 64) shows the same position in which less civil service employment occurs in rural areas.

Inter-Departmental Business Register 2017/18 shows that 16.8% of people employed in rural local units of businesses work in 'education, health and social work', with a comparison of 21.9% for urban.

Inter-Departmental Business Register 2017/18 shows that 4.2% of people employed in rural local units of businesses work in 'public admin and defence; other services', with a comparison of 6.4% for urban.

There are other industry types in which rural areas have higher proportions of people working. Where lockdown restrictions are effecting these industries disproportionately, national and local bodies with an interest might look at ways of supporting these industries going forward.

Taking data from the Inter-Departmental Business Register 2017/18:

- the proportion of people employed in local units of businesses who work in 'accommodation & food service activities' stand at 10.1% rurally and 7.0% for urban areas

- the proportion of people employed in local units of businesses who work in 'manufacturing ' stand at 11.1% rurally and 7.5% for urban areas

- the proportion of people employed in local units of businesses who work in 'agriculture, forestry and fishing ' stand at 7.5% rurally and 0.2% for urban areas

The majority of employees in rural areas work for small and medium enterprises. The Inter-Departmental Business Register shows that the majority of people employed in rural local units of registered businesses work in businesses of between 10 and 49 employees (29.4%). In contrast, for urban areas the majority work in businesses with 250 and more employees (28.8%). 71.5% of all employment by registered enterprises is by Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) for rural areas. The proportion in urban areas is 41.4%. Predominantly rural local authority areas have more registered business per 10,000 population than England on the same basis. The administrative burden of dealing with a higher proportion of SMEs in rural areas needs to be considered in any roll-out of assistance.

Capital investment (spending money on fixed assets) per employee is lower in predominantly rural local authority areas than England overall. In 2016 capital investment per employee in predominantly rural areas was around 93 per cent of the level for England as a whole. If investment is not available to rural business at the same rate as urban business after the Covid-19 shutdown, this will naturally slow the rate of economic rejuvenation in rural areas.

On examining the Council Taxbase for 2019, predominantly rural authorities on average have 1.8% of properties on their valuation list classed as second homes. This percentage stands at 0.8% for predominantly urban authorities. Where second homes are not being visited due to the lockdown and travel restrictions, it follows that local businesses will suffer economically. Whilst 1.8% may not seem high, some Parishes have significantly high levels of second homes, closer to 50% and lack of visitors will have a major impact on local tourism, the economy and small businesses.

From DEFRA's Statistical Digest of Rural England, March 2020 Edition, in 2017/18 there were 63,800 tourist related businesses registered in rural areas, with total employment of 0.6 million. As a proportion of total employment, in rural areas this accounted for 14% of employment compared with 11% in urban areas. For settlements in sparse settings, employment from tourism related registered business was higher still at 22% of total employment.

Clearly for businesses that rely on tourism and visiting second home owners, income during peak months is essential both short term and longer where reserves are needed to get through winter months where trading stops.

Access to Key Services

Accessing key services, and inversely bringing key services to those in the community who now need to be shielded, is a significant issue for rural communities. Shielding will be essential for some residents of rural communities both currently and into the foreseeable future. It is therefore important that the delivery of service is considered and adapted with reference to the rural situation so that everyone can access the services they require.

Now more than ever broadband is really important for accessing a wide range of activities, including to a much greater extent than ever before, social interaction, home working and GP appointments. Again taken from DEFRA's Statistical Digest of Rural England, March 2020 Edition, average broadband speeds in rural areas tend to be slower than those in urban areas. In 2018 the average speed in rural areas was 34Mbit/s compared with 53 Mbit/s in urban areas, 7% of premises in rural areas were not able to access a decent broadband service, however 83% had superfast broadband availability (although this lags behind urban areas at 98%). Broadband provision worsens the more rural an area is, so for areas categorised as 'rural hamlet and isolated dwellings in a sparse setting' the percentage of premises unable to access a decent broadband service rises to 35%. In these new times of social isolation and shielding, pockets of England with low service quality need to be identified and appropriate actions taken to prevent exposing the most vulnerable to unnecessary danger.

Shielding necessitates essential supplies to be delivered to the recipient. The additional resource that this might take to assist someone living in a rural situation can be illustrated by the distance travelled per person per year for the purpose of shopping. Department for Transport figures for 2017/18 show that for someone living in what is classified as an 'urban conurbation', the distance travelled is 508 miles, for someone living in a 'rural village, hamlet and isolated dwelling', the distance is 1,349 miles. Whatever services are provided to assist those shielding, providers will need to consider the longer journeys in providing them and the additional cost that this might involve.

If the economy shrinks and jobs density becomes smaller, those living in rural areas may be required to travel further to access centres of employment. Department for Transport figures show that in 2017 the average minimum travel time to reach a centre of employment with 100 to 499 jobs by public transport or walking was 7.5 minutes in urban areas, yet 18.5 minutes for rural residents. Fewer jobs would push people to look for employment further afield. Without an affordable, fit for purpose transport system, this would leave rural residents at a disadvantage in securing employment, and would cast adrift anyone unable to afford private transport.

Conclusions

This is clearly not an exhaustive list of the challenges that dealing with coronavirus brings to rural residents and communities, but is presented to illustrate the additional consideration that any intervention in a rural community requires. Immediate and longer term plans are being made to assist communities by national and local agencies, and it is essential that these plans take into account the situation locally including their rural nature and the unique perspective that that brings.

To discover more about your local authority area and what makes it unique, do visit the RSN Member Insight and Analysis section at:

https://rsnonline.org.uk/category/member-insight-and-analysis